Old footage, new fire: why a 2010 audition took over film Twitter

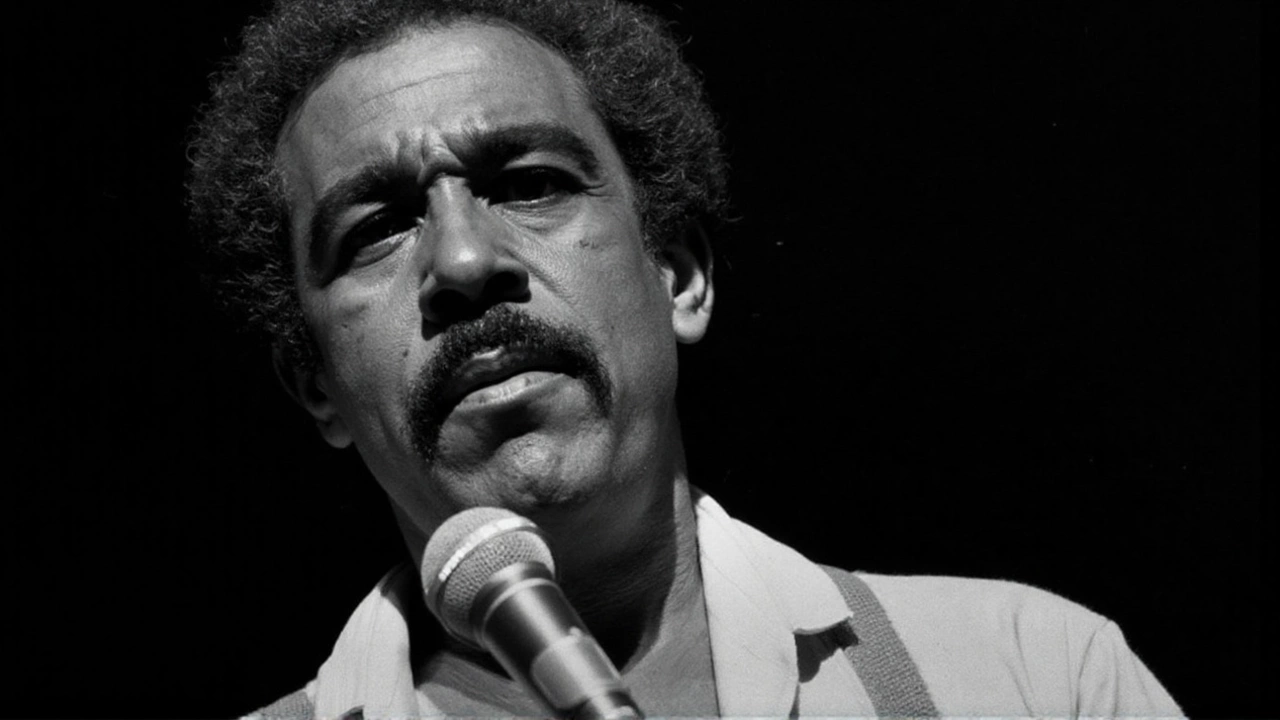

A 14-year-old video just reopened one of Hollywood’s trickiest casting debates. A screen test of Marlon Wayans as Richard Pryor, shot around 2010, resurfaced online and instantly split fans over who should play the most influential stand-up of the modern era. The footage isn’t tied to an active film, but it didn’t matter—within hours, the argument was back: Wayans or Mike Epps?

The case for Epps came fast and loud. Many viewers said he looks closer to Pryor and leans naturally into Pryor’s storytelling rhythm—sharp, confessional, and unpolished in a way that feels lived-in. Others called Wayans a talented performer but argued his comedic instincts skew more toward physical, high-energy bits than Pryor’s bruised honesty. One widely shared quip boiled the sentiment down to a gut-check: if you’re not at least in the neighborhood of Pryor’s funny, you’ll get exposed on screen.

There’s a catch, though: the clip everyone is debating is from a version of the film that no longer exists. Back in 2010, director Lee Daniels tested Wayans for a Pryor project. A few years later, the same iteration pivoted and brought in Mike Epps for the lead. By 2014, the entire production had stalled amid creative friction and disputes involving Pryor’s widow, and the project went cold. The current firestorm is about a ghost of a movie that never got made.

The whiplash isn’t new. The Richard Pryor biopic has been orbiting development for more than a decade, attracting big names and then losing momentum. Eddie Murphy’s name came up early and often. Damon Wayans was floated. Epps rose, fell, and rose again as the perceived front-runner. Directors circled and moved on. Studios kicked the tires. At different points, the estate’s involvement and creative control became sticking points. The result: years of headlines and no greenlight.

So why do fans keep rallying behind Epps? Start with resemblance. On screen, a close match buys credibility before a line is delivered. Add to that Epps’ stand-up background—he knows the weight of silence, the jagged pacing of a bit, and how to let pain breathe without turning it into melodrama. Pryor’s material rode the edge of humor and hurt; a performer who can sit in that tension feels like a safe bet.

Wayans, for his part, isn’t a lightweight. He’s done serious work—Requiem for a Dream remains the go-to example—and he showed range again in recent dramatic roles. He’s also meticulous about craft. Audition footage, especially from a decade ago, is a blunt instrument; no hair, makeup, or final script, and often no time to dial in a voice. A lot of great performances would look shaky at the screen-test stage. That context gets lost in a viral clip.

What it takes to play Pryor—and why the film keeps stalling

Richard Pryor isn’t just a role to play; he’s a system to decode. He reinvented stand-up by mining trauma for laughs without sanding off the splinters. He had a dancer’s physicality, a voice that could slip from swagger to whisper, and an ability to make a room hear its own secrets. Getting that right means more than a wig and a mustache.

- Voice and musicality: Pryor’s timing wasn’t built on punchlines alone. He stretched silence, clipped phrases, and used misdirection like a jazz break.

- Physical truth: The way he moved—loose shoulders, shifting stance, quick pivots—sold the bit before the words did.

- Vulnerability: The laughs came from candor. If the performance feels guarded, it collapses.

- Era-hopping: A biopic has to cover early club work, superstardom, and the later years battling illness. That’s three different men in one role.

There’s also the script problem. Pryor’s life includes addiction, health struggles, and public controversies, alongside creative breakthroughs that changed comedy worldwide. A film has to show the mess without turning it into misery porn—and still be funny. That balance is hard even before you layer in estate approvals, music and performance rights, and the pressure of portraying a cultural icon who still defines the job for today’s comics.

Industry folks will tell you the casting debate is only half the battle. Financing a music-and-comedy biopic is expensive. You need rights to stand-up material, concert footage, and period settings across multiple decades. You also need to convince audiences under 30 why Pryor matters now. That’s doable—the DNA of contemporary stand-up traces straight back to him—but it demands a script that feels urgent, not historical.

The 2010 Daniels version showed how fragile the package can be. It had heat, a lead taking shape, and then hit the wall. Years later, new development waves rolled through—fresh scripts, new producers, another round of casting whispers—but nothing landed in production. Each cycle revives the same question: is there a definitive version of this story everyone can agree on?

Social media doesn’t make that easier. Once a clip trends, it flattens the nuance. Fans rally behind the face that looks “right,” or a performance that matches their memory of Pryor. But a definitive screen Pryor probably won’t be an impression. It’ll be interpretation—anchored in truth, edged with discovery, and brave enough to show the parts of Pryor that still sting.

That’s why the Epps vs. Wayans debate keeps circling back to comedic DNA. Epps feels closer to Pryor’s grounded storytelling; Wayans brings sculpted technique and dramatic control. Either path can work with the right director and script. It comes down to a creative choice: do you chase mimicry, or trust an actor to pull Pryor’s essence through their own instrument?

One more wrinkle: the arc. Pryor’s later years, including his battle with multiple sclerosis, force a performance to shift from kinetic stage magnetism to a different kind of presence—quieter, reflective, still sharp. Not every comedian-actor can turn down the volume and keep the power. That’s a tough ask when the first act is built on live-wire electricity.

There’s a practical timeline issue too. The longer a project waits, the more turnover you see—new studio leadership, new priority lists, and a new generation of viewers. The window to make a biopic that feels like an event can close if it drifts for a decade. That’s where the Pryor project sits now: lots of goodwill, plenty of talent interested, and a proven audience curiosity—yet no cameras rolling.

So the clip of Wayans did what the internet does best: it turned a dormant project into a real-time casting referendum. Fans want a Pryor movie and they want it to feel right. Epps has momentum with the crowd. Wayans has defenders who think the tape undersells what he could do with a full production. And somewhere, a producer is watching the traffic numbers and wondering if this noise can finally be turned into a greenlight.

If there’s a lesson from this round, it’s simple: the actor matters, but the plan matters more. Pryor’s story needs a script that breathes, an estate that’s aligned, and a director who can stage stand-up without killing its danger. Nail those, and the right lead—whether it’s Epps, Wayans, or someone who hasn’t tested yet—will have room to find the man behind the legend.